Why The US Air Force Will Reduce Aircraft Maintenance AFSCs From Over 50 To 7

The USAF aircraft maintenance program is downsizing the number of job specialties from 50+ to seven. This is in response to the three challenges identified by USAF leadership:

- Recruiting and retention problems;

- Preparing for war with a near-peer adversary;

- Reduce the number of maintainers deployed down range for mission generation during combat operations.

This article focuses on changes being made to the aircraft maintenance Specialty Codes, targeted for 2027.

The USAF’s conundrum in managing job classifications

As a USAF Vietnam Veteran and military aviation historian, I have witnessed first hand the evolution of the Air Force Specialty Code (AFSC) system. For reference, an AFSC has the same meaning in the Air Force as Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) does in the Army.

All of the service branches are in a never-ending evolution of change in all aspects of their duties and personnel. The Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard have some unique training and skill requirements that are intrinsic to their military role, and each service member must be proficient in.

Photo: Airman 1st Class Brooke Moeder l U.S. Air Force

The Army and Marine Corps, for example, have the majority of personnel involved in ground combat roles. The Navy and Coast Guard have the majority of their people serving in a waterborne billet. These service members have major training components for skills needed in ground combat, or shipboard duty. Training for these skills do not change very often.

On the flip side, neither the Air Force nor the Space Force have any core training requirements that are unique to their service branch. For example, there are no basic criteria for airmen to know anything about airplanes or flying. Similarly, Space Force guardians do not receive generic training on satellites or communication systems.

The majority of Air Force AFSCs involve highly complex equipment and systems. Compared to other service branches (sans the Space Force), the Air Force has the highest percentage of enlisted personnel involved in high technology jobs. For the Air Force, it is a neverending evolution of increasingly complex work for maintenance technicians and flight crew.

The Air Force’s aircraft maintenance jobs in WW II

Twenty-five years prior to World War Two, airplanes were introduced to the battlefields of W.W. I. Back then, military aviation had two careerfields: the men flying planes and the men fixing them.

Although W.W. I maintenance officers and NCOs may have recognized the value of specialized jobs, such as an engine mechanic, the aircraft maintenance mechanic remained a one-size-fits-all careerfield until the early 1920s.

Photo: Liz Cueto l National Museum of the Air Force l U.S. Air Force

During the interim period between the two world wars, military airplanes became more complex, which gradually pressed maintenance work to shift to multiple job classifications. During WW II, the following aircraft maintenance AFSCs were used:

- Engine Mechanic

- Aircraft Mechanic (maintenance crew chief)

- Aviation Machinist (it was not uncommon for aircraft spare parts to be made from scratch in the field)

- Sheet Metal Mechanic

- Cockpit Instrument Technician

- Propeller Repairman

- Aircraft Electrician

Five years later, during the Korean War, the following aircraft maintenance AFSCs were added to the W.W. II jobs. Each of these duties was formerly done by one of the AFSCs identified from WW II.

- Radio Repairman

- Jet Engine Mechanic

- Weapons & Munitions Technician

- Aircraft Ground Support Equipment Repairman

The general philosophy amongst Air Force human factors experts was that legacy AFSCs had full plates. They were reticent to push any occupation backward to a generalist instead of a specialist. It was clear that in the 1950s and 1960s, the Air Force loosely believed that increased systems complexity equaled more specialization.

Aircraft maintenance policy during the Vietnam Era

The Air Force also addressed enlisted personnel on flying status; there were no dedicated AFSCs for enlisted professional aviators.

Enlisted airmen serving on flying status came from applicable maintenance AFSCs. For example, Flight Engineers (FE) on C-130s had to come from the Aircraft Mechanic (crew chief) AFSC.

Crew Chiefs who chose to accept an FE position kept their Aircraft Mechanic AFSC and their flying status was identified by the letter “A” as a prefix to their AFSC. There was no enlisted professional airman program back then. This meant there was no guarantee that an airman on flying status would remain in that capacity when they received orders for a permanent change of station.

Photo: Sr. Airman Mackensie Cooper l U.S. Air Force

This policy changed slightly when the B-52 bomber and KC-135 tanker entered the USAF inventory in 1955 and 1957, respectively. Both of these aircraft had an enlisted crew member. The B-52 had an aerial gunner for the tail turret, and the KC-135 had a refueling boom operator. The Air Force determined that these two AFSCs would be career professional aviators.

In the 1980 timeframe, the USAF decided to adopt the policy of an enlisted professional aviator workforce. Simply put, you can fix the plane or fly it, but not both. This led to a new set of AFSCs for enlisted aviators.

The Vietnam Era saw further diversification of aircraft maintenance by adding the following maintenance AFSCs:

- Corrosion Control Technician

- Airborne Radar Technician

- Aircrew Safety & Environmental Control Technician

- Navigation Systems Technician

- Avionics Technician

The Vietnam War strained the Air Force’s equipment maintenance system. The system was three tiers:

- Organizational maintenance (occurs at a local level wherever the point of use is)

- Intermediate maintenance

- Depot maintenance

Every piece of equipment the Air Force owns has been evaluated to determine how it will be maintained. Everything at least has organizational maintenance. For example, replacing an air filter on a jet engine.

The air filter’s maintenance plan specifies to remove and replace it with a new one at the organizational level. The maintenance plan states both Intermediate and Depot maintenance functions for the filter are “N/A.” The maintenance plan states the old air filter needs to be put in the trash.

Another example is a power supply for a plane’s radar system. The power supply can be repaired locally where the radar system is. If that is not possible, it can be sent to a centralized power supply repair shop for intermediate maintenance. If they cannot fix the power supply, it is sent to the repair depot. In the case of the power supply, the repair depot is not a military shop. The depot is the OEM that originally made the power supply.

In order to facilitate the maintenance/repair planning of every system and sub-system, consideration must be given to who will do the work at the three levels. The Intermediate maintenance level was fairly new during the Vietnam Era.

Most equipment and its responsible maintainer either fixed a broken piece of equipment themselves at the organizational level, or it was sent out for Depot repair. Most Depot repairs took two to three months before the item came back to the organization that owned it.

At the 2024 Air Force Association’s “Air, Space & Cyber Conference,” Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force David Flosi said:

“The impetus for these changes is the possibility of conflict against China or Russia, where smaller groups of Airmen will have to generate aircraft from farther-flung airstrips. We’ll be contested in the air, on the ground, in the information environment. Supply chains are far more difficult in the Indo-Pacific theater, so we need to put the smallest number of Airmen into harm’s way and achieve the maximum capacity out of each one of them.”

Until the Air Force introduced the Fairchild A-10, and the General Dynamics F-16 in the mid-to-late 1970s, the concept of “intermediate maintenance” was mostly just that – a concept.

The massive drain of Air Force personnel to staff all the billets in Southeast Asia was a wake-up call that was not easily fixed. For nearly all types of aircraft equipment and its maintenance in the field, the gap between fixing something locally at the organizational level vs depot repair, was huge.

Photo: U.S. Air Force

What local maintenance shop was comfortable telling a wing commander (a colonel) that he had a half-dozen airplanes that were unflyable because they had broken equipment that was sent in for depot repair and there were no functional units in the supply system?

I am not telling him!

One of the most labor-intensive tasks maintainers do on the flight line is uploading munitions to mission aircraft. A common Boeing B-52 bomber munitions load-out is 108 500 lb bombs, as shown. This bomb load takes six airmen up to three hours to complete!

Dealing with an outdated aircraft maintenance system

Until the Air Force received their newly anticipated aircraft with the intermediate maintenance system baked-in, maintenance personnel had to be trained in technical school to be able to troubleshoot and repair everything in a given system.

Related

Agile Combat Employment: What Is The ACE Strategy Of The US Air Force?

The United States Air Force (USAF) uses Combat Employment (ACE) to work with NATO allies.

It ran the gamut – from the simplest task of removing/replacing the unit from an aircraft, to troubleshooting and fixing the problem down to the lowest nut or screw, or replacing an electronic component on a circuit board with a soldering iron!

Highly technical AFSCs, like Jet Engine Mechanic, or Radar Repair Technician, had technical school training of 40 weeks or more! Add in basic training, and any unit needing one of these AFSCs had to submit a personnel requisition a year in advance. Keeping the student pipeline full at all times was a must. The existing aircraft maintenance system through the end of the Vietnam War was much like a bad habit or addiction.

You knew the addiction had to stop, but, if it could not be treated properly, the only way to maintain some semblance of functionality was to keep doing what everyone knew needed to change until the problem could be dealt with properly. This meant further specialization to prevent technical schools from keeping airmen in classes even longer than before.

The Intermediate Maintenance System (IMS) arrives

In the early development stages of the A-10, and F-16, the Air Force Logistics Command decreed that all new “clean sheet” aircraft development programs had to adopt IMS.

The IMS concept was similar to the dysfunctional three-tier system that failed, but with the following important changes.

-

Level One – Organizational Maintenance

- Aircraft maintenance is done on a modular basis. The A-10, and F-16 were designed with as much equipment and systems as possible in standardized housings called Line Replaceable Units (LRU).

- In Air Force jargon, LRUs were a fancy name for “black boxes.” LRUs do not contain anything that is end-user serviceable. Local maintenance shops could only remove and replace an LRU on the plane, or make an adjustment if it is accessible from outside an LRU.

- All systems and equipment had built-in test capability that flightline maintainers could use for fault isolation.

-

Any maintainer AFSCs that have their system(s) housed in LRUs are eliminated from local maintenance organizations.

- The eliminated AFSCs were replaced by an integrated avionics specialist.

-

Level Two – Intermediate Maintenance

- Maintenance tasks formerly done locally, including work done inside an LRU, moved to a new function, the intermediate maintenance back shop.

- Each of the new aircraft have its non-functional LRUs sent to the intermediate maintenance back shop. The basis for repairing LRUs at the intermediate maintenance back shop are multifunctional test stations known as a Versatile Depot Automatic Test Station (VDATS).

- VDATS were designed as a set of four stations grouped by type of equipment. One station was for Accessories, including systems such as: electrical, environmental, egress, fuels, hydraulics and pneumatics. A second station tests the various avionics assemblies. The third station covers systems that transmit and/or receive external signals, such as radar, radios, and infrared sensors. The fourth VDATS tests all propulsion equipment.

- Each VDAT Station has an AFSC-specific specialist trained to test, troubleshoot and repair the applicable UUTs (unit under test).

-

Level Three – Depot Repair

- Any equipment that cannot be tested and repaired at the intermediate level is sent out for depot repair. Depot repair can vary from one piece of equipment to another. One LRU may have its depot repair done at one of the Air Force’s Air Logistics Centers. Some equipment may require depot repair by the OEM. Whether an LRU sent in for depot repair was done at the Air Logistics Center or sent out to the OEM to do it, was immaterial to the specialists working in the intermediate back shop. All broken LRUs were always sent by default to the same depot at the Air Logistics Center, and they knew how to handle an LRU’s repair.

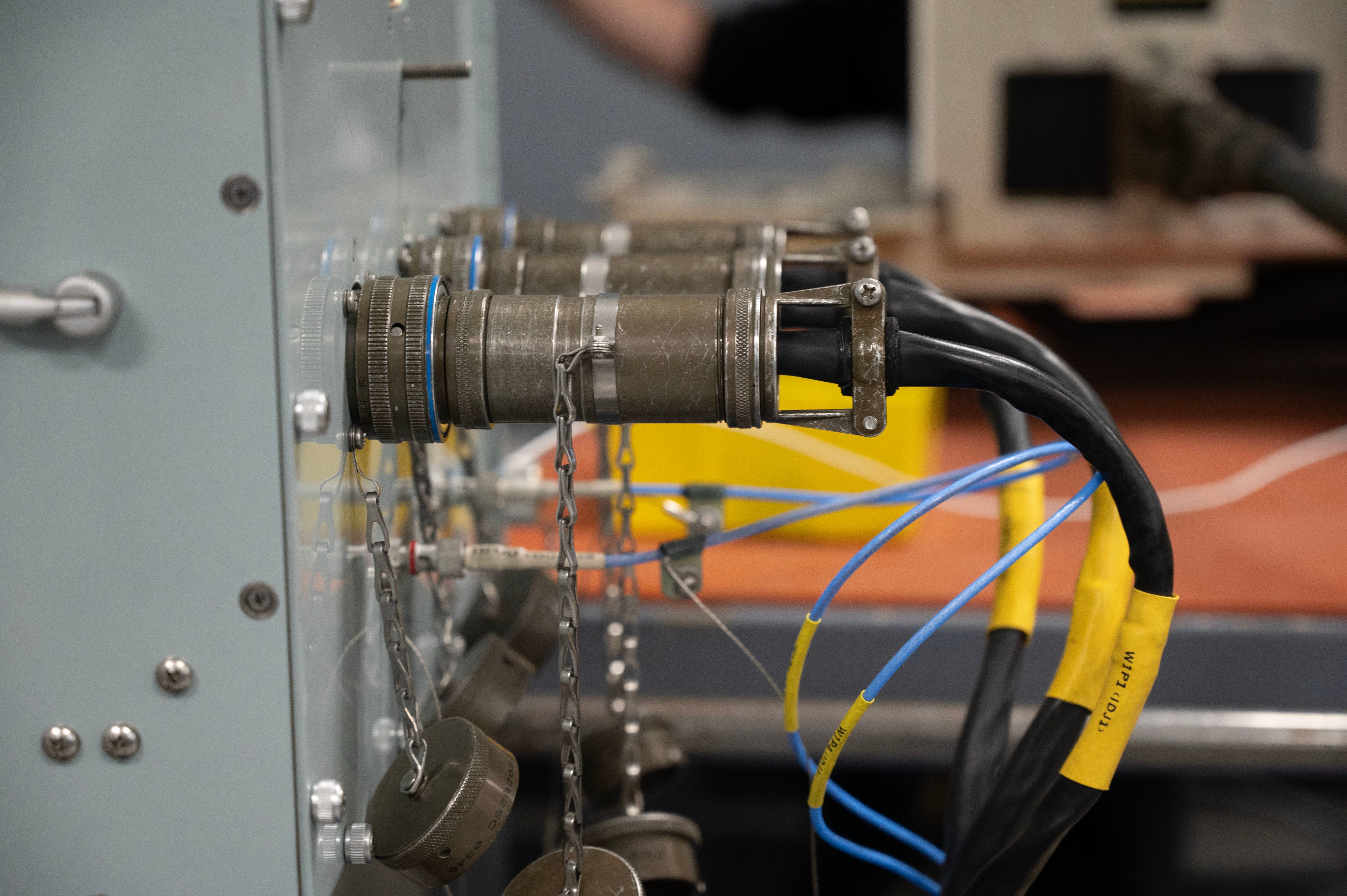

Photo: Teresa Vogt l Air Force Life Cycle Management Center l DVIDS

A Versatile Depot Automatic Test Station is an extremely complex system. Using the word “automatic” to describe a test station is a bit overstated. The test station primarily does three things:

- The black box on the left with the red and yellow connector caps is an Interface Test Adapter (ITA). The ITA is where the UUT (unit under test) is connected to the test station via a set of cable harnesses that provide the same electrical and signal connections the UUT has aboard the aircraft;

- The test station simulates all of the input and output signals the UUT normally sees;

- The test station includes (gray colored) standard diagnostic test equipment, such as an oscilloscope, spectrum analyzer, etc. The test station assists the technician in isolating the fault.

Intermediate maintenance solves one problem, but creates others

Prior to implementing intermediate maintenance back shop, Air Force technical schools were too long, and the number of airmen needed for overseas deployment was excessive. The intermediate maintenance back shop would reduce the number of deployed maintainers by 75%.

Ultimately, the intermediate maintenance back shop was implemented in flying wings by two types of squadrons: On-aircraft maintenance called the “Aircraft Maintenance Generation Squadron” (AMXS) and off-aircraft maintenance called the “Maintenance Generation Squadron” (MXS), which seemed to be working okay, until Desert Storm arrived.

Photo: Teresa Vogt l Air Force Life Cycle Management Center l DVIDS

Maintenance generation squadrons are where intermediate maintenance equipment and VDATS technicians are assigned, and not part of day-to-day aircraft maintenance generation. Flying squadrons were not deployed to the Middle East as part of a complete wing. An F-16 fighter wing had three fighter squadrons, an aircraft maintenance squadron and an off-plane (intermediate) maintenance squadron.

One or two fighter squadrons from the same wing would be deployed with a detachment of maintainers from the cognizant aircraft maintenance squadron. No maintenance squadron back shop VDATs or test station specialists were deployed because it would strip the home wing of its intermediate maintenance capability.

Intermediate maintenance problems during Desert Storm were handled on a case-by-case basis. Making permanent changes to the maintenance system during combat operations was ill-advised. The 20+ years of deployment during the Global War on Terror (GWOT) created fewer maintenance problems by standing up expeditionary wings overseas with a deployed set of VDATS and test specialists.

Changing from GWOT to near-peer military operations

In 2018, America’s National Security Strategy was updated to reflect a shift from a counterterrorism focus to a two-front war against near-peer adversaries. The needed changes in American warfighting have been significant and ongoing.

An example of the changing military strategies is the Marine Corps. Ever since Vietnam, the Marines have adopted operational practices that make the Corps nearly interchangeable with the Army.

Refocusing the Marine Corps on their QRF (quick reaction force) capability and not a “me too” infantry like the Army, required them to divest equipment that did not fit the definition of a QRF. To that end, the Marines discontinued armor operations by surrendering their tanks to the Army.

One of the most important changes being implemented by the Air Force is called ACE (agile combat employment)

During the Vietnam War, the US Air Force had seven air bases in Thailand and 10 air bases in South Vietnam. The bases in Thailand were never attacked. On the other hand, the bases in South Vietnam were attacked 475 times during the war. The bases were attacked from the ground; the enemy had no air combat capability in South Vietnam. Had there been an enemy airborne threat, the 475 air base attacks would have been magnitudes higher.

Photo: Staff Sgt. Val Gempis l DVIDS

Stating the obvious, when US forces withdrew from South Vietnam and Thailand, the 17 air bases were relinquished, too.

In addition to these lost bases, the Air Force lost its huge installation, Clark Air Base, in the Philippines in 1991. (photo below). The Air Force also left their bases in Taiwan, and two bases in Japan.

With limited basing options in the western Pacific, if China invades Taiwan, where will the USAF put its aircraft moved into the region to defend Taiwan? The Philippines are allowing Air Force assets to return, and other basing discussions are underway with other regional countries. It is fair to say, however, that the 20+ air bases America had during the Vietnam War are not coming back. It is unlikely that even five or six bases can be obtained.

The reality is that the handful of bases the Air Force will have access to will be extremely crowded. It is also a reality that China will attack those bases. The Air Force has to have a plan to mitigate aircraft losses due to enemy attacks – this is where the policy of Agile Combat Employment comes in.

Agile Combat Employment (ACE) – explained

Boiling down ACE to its basic premise, it is an aircraft dispersal strategy. Anticipating that an adversary would attack U.S. air bases, ACE planning predetermines which aircraft, maintainers, and support equipment will be dispersed, including the confidential location.

If you have ever wondered about stories and videos of military aircraft landing on highways, roads, and open land, it is not so much about practicing an emergency landing due to an inflight incident as it is about moving personnel and assets out of harm’s way.

Photo: TSgt. Carly Kavish l 1st Special Operations Wing l DVIDS

ACE requires significant preplanning, including site selections, which aircraft will go where, an ACE maintenance support kit, and assigning maintainers to the various dispersal sites.

ACE’s effect on enlisted maintenance airmen

When intermediate maintenance concepts were first introduced, it definitely reduced the number of different maintainer AFSCs needed for on-aircraft flight line maintenance. Over the ensuing decades of new aircraft entering the USAF fleet, the aircraft maintenance AFSCs required adjustment.

There are no two aircraft models with similar maintenance programs. The new planes include: the B-2, C-17, CV-22, E-8, HH-60, F-22, MC-12, and F-35. When the F-22 and F-35 entered the inventory, maintenance AFSCs had to be bifurcated into 4th-generation fighters and 5th-generation fighters. The AFSCs splintered again when drones became operational.

Photo: Joshua Seybert l 911th Airlift Wing l DVIDS

Fast-forwarding to the 2020s, aircraft maintenance AFSCs are over 50, and it exceeds the number of AFSCs used on legacy aircraft prior to introducing the A-10 and F-16 over 40 years ago. Understanding the need for Agile Combat Employment in the face of near-peer conventional warfare makes it essential for maintenance airmen to be more versatile than we have seen since the Korean War.

Air Force Headquarters published a revised aircraft maintenance policy in January 2025 that addresses how aircraft maintenance personnel can best support keeping planes in the air in an up-tempo, altered operational environment.

The analysis behind the new aircraft maintenance policy surveyed all of the AFSCs involved in generating mission-ready aircraft. The researchers discovered that when maintenance hours were totaled by AFSC, then a grand total, it was determined that 80% of the hours spent on aircraft maintenance were attributable to only 20% of the AFSCs.

Implementing ACE, if needed, would create a shortage of the AFSCs at dispersal sites that do 80% of the work. It is very clear that the maintenance workforce had to change.

Aircraft Maintenance Future Force Design

Enlisted maintainers come into the aircraft maintenance AFSCs as a Generalist. The Generalist track is for E-1 Airman through E-4 Senior Airman. This is where 80% of the work is done.

The work includes end-of-runway checks before launch, ground handling postflight, preflight, thru-flight, special inspections, and phase inspections. Performs sortie generation operations and hot pit refuels. Advises on problems maintaining, servicing, and inspecting aircraft and related aerospace equipment.

Upon promotion to Senior Airman, they make a Specialist AFSC selection and are sent to technical school for it. The specialist areas include:

- Avionics and Electrical, which combines avionics with the electrical side of the Environmental and Electrical (E&E) specialty

- Aerospace Ground Equipment, which will look the same as it does now

- Advanced Mechanical, which combines crew chiefs, fuels, hydraulics, and the flight line side of engine maintenance

- Crew Support Systems, which combines ejection seat systems with the environmental side of E&E

- Fabrication, which combines aircraft structural maintenance, aircraft metals technology, and nondestructive inspection.

- Intermediate-level engines, for maintainers dedicated to intermediate-level engine maintenance.

For the airman’s remaining time as an E-4 Senior Airman, through E-5 Staff Sergeant to E-6 Technical Sergeant, they can do all of the Generalist duties, and the Specialist duties they have been trained for.

After promotion to Technical Sergeant, two options are available: remain in the specialist AFSC, or be trained to become a cross-functional technical expert for all six AFSCs.

Photo: U.S. Air Force

After promotion to Master Sergeant, two options are available: receive leadership training that carries through Chief Master Sergeant, or remain a cross-functional technical expert. If the airman remained in their specialist AFSC, and did not pursue the technical expert track, they can choose to go to a technical expert school now, or simply attend leadership.

Closing out the discussion

From a warfighting standpoint, the primary mission for all maintainers is to facilitate the generation of safe, reliable and mission-ready aircraft. When a plane returns from a mission, maintainers do whatever it takes to turn the plane around to make it ready for the next mission.

The new maintenance AFSC scheme will ensure that regardless of which maintainers are available for the mission, a generalist or one of the specialists, they can all preflight, launch and recover aircraft, including maintenance debriefs with the aircrew and post-flight inspection.